BLOG

Where Strategy, Innovation, and Equity Meet— Explore the Ideas Shaping Tomorrow’s School Leaders.

ALL THINGS AI

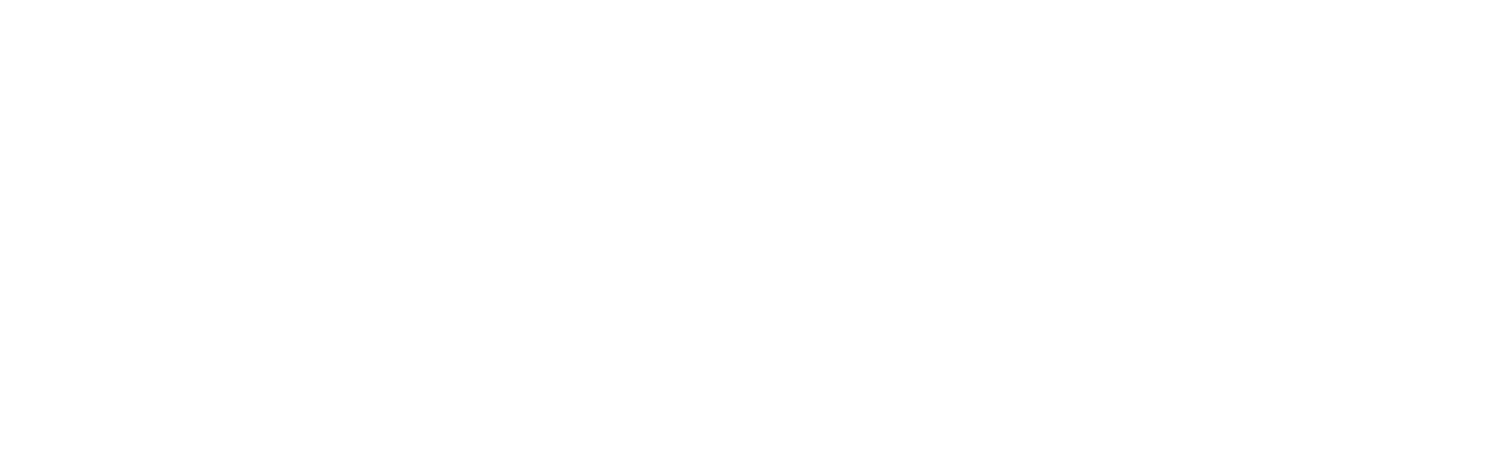

Academia María Reina (AMR), a Catholic girls' school in Puerto Rico, knew its students were already using AI on their phones long before adults had a plan for it. Teachers worried about cheating and the loss of "real" thinking. Students treated AI as a shortcut, something "there to do everything for you," as technology facilitator Anyelisa Mejías observed. Instead of waiting, AMR invited Forward Learning, a regional professional development and learning environment provider serving schools across Puerto Rico, to face AI head-on. They pursued two Middle States Association (MSA) Responsible AI in Learning (RAIL) endorsements as partners.

Have you ever played whac-a-mole? The game used to be a mainstay of arcades and boardwalks. One mole pops its head up. You strike it with a mallet, which sends it underground. But as soon as it disappears, a different mole pops up somewhere else on the gameboard. Repeat until time runs out on the game. AI in schools is a whac-a-mole problem.

According to conventional wisdom, students currently in high school are part of Gen Z or Gen Alpha. Gen Z, as in “Zoomers,” because many experienced school on Zoom during the COVID pandemic. Gen Alpha, as in “alpha,” because they are the first generation born entirely in the 21st century. I see them as Gen AIC, because they are coming of age amidst the two great paradigm shifts in school: AI and COVID.

When generative AI surged into schools, Bahrain Bayan School initially responded the way many did: with guidelines and one‑off trainings aimed at keeping pace with a fast‑moving technology. Joining Middle States’ Responsible AI in Learning (RAIL) endorsement shifted that response from reactive to structured, helping the school design AI use that is human‑led, ethically grounded, and sustainable.

It’s hard enough to prepare young people for an AI-shaped future. But how do you do that while preserving their identity?What about strengthening that identity? Those are the stakes at Bahrain Bayan School, where most students are Bahraini and every decision about curriculum, technology, and student support is a decision about the country’s future. With AI advancing at an exponential rate, Bayan sought a solution in the Middle States Responsible AI in Learning (RAIL) endorsement in AI Literacy, Safety & Ethics. The end result? Bayan amplified their core identity using the endorsement’s implementation framework, called the Pace Layer Model.

In 2023, Choate Rosemary Hall, an independent boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut, faced the challenge every school was grappling with: how to respond to generative AI. Like many schools, Choate had faculty across the spectrum. Some were experimenting enthusiastically. Others were deeply concerned. The easy path would have been to issue a quick policy and hope it settled things. Instead, they chose a different approach, one grounded in their mission, built on trust, and designed to bring everyone along.

In conversations with education leaders across the Middle States network, one question keeps coming up: “How do we embrace AI without sacrificing what makes learning deeply human?”

Globally, education leaders are grappling with similar AI readiness questions, as reflected in UNESCO’s comprehensive new anthology, AI and the Future of Education: Disruptions, Dilemmas and Directions (UNESCO, 2025).

Excel is pairing AI with competency checks so students can show what they know and get to the right next step. They will expand their in-course tutor and teacher-facing supports with the same closed-system guardrails.

“AI will help students demonstrate competency and then challenge them in ways that fit their learning style” — Charlie Buehler Hoard, COO

LEADERSHIP INSIGHTS

Some leaders impress you with their intelligence. They seem to have mastered every angle of their work.

Other leaders impress you with their emotional intelligence. They make sure people feel seen and known and cared for.

And then there is a leader like Ren Parikh, the founder of Ideal Institute of Technology (“Ideal”). He’s more like a force of nature…

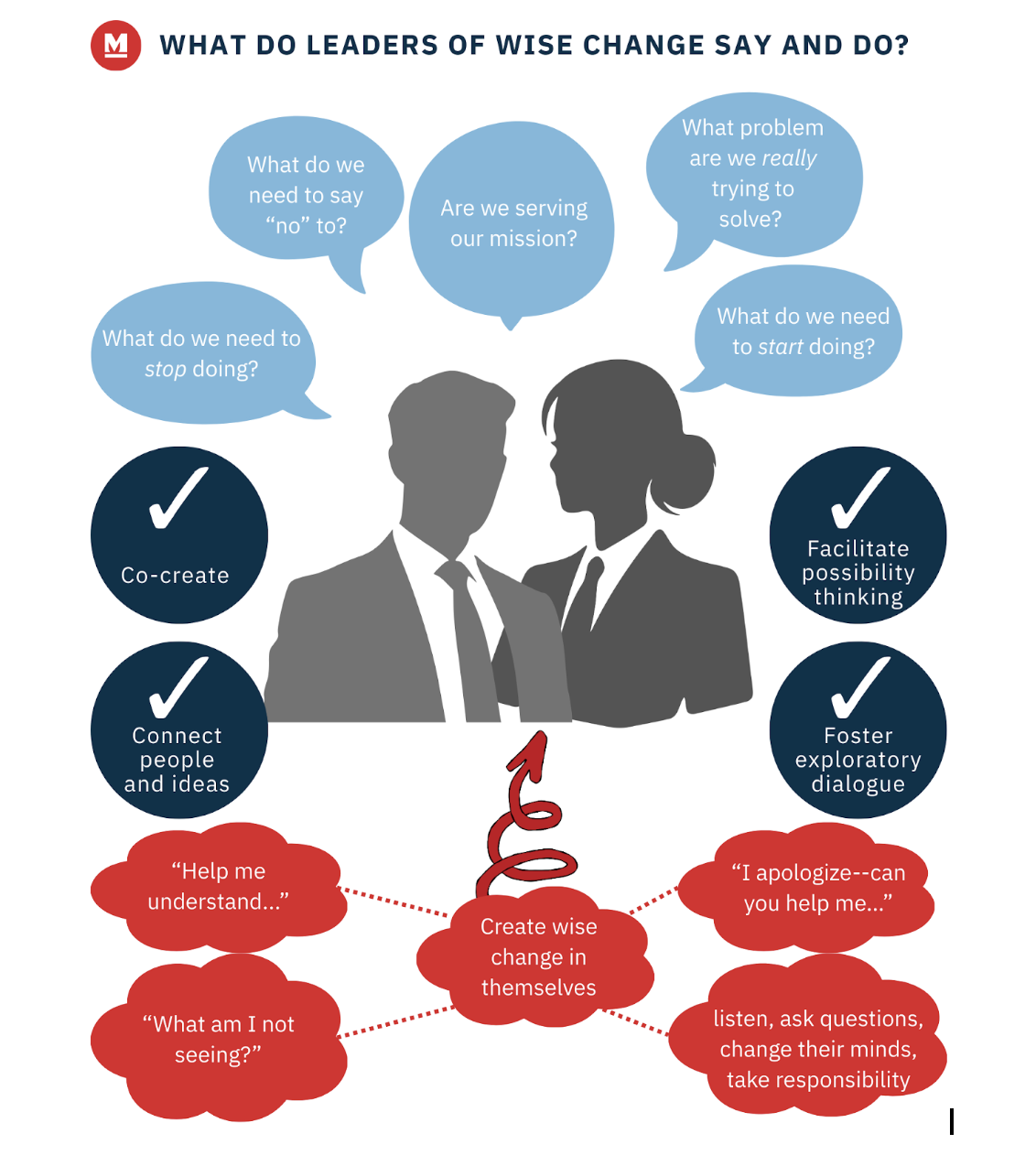

My recent conversation with Adam Bryant has me thinking about leading change in schools. Three particular things stand out from that chat:

Focus on “impact” rather than “intent.” Adam pointed out that if we over-index on purpose and mission (“intent”), we may lose sight of the reason to lead: to create positive impact.

We know that teachers can expect feedback on their craft substantially less than 1% of the time. Yet to foster genuine growth and development, merely increasing touch points is necessary, but insufficient.

SCHOOL CHANGE + TRANSFORMATION

You have heard us talk about wise change a lot this past year.

But what does it mean, exactly?

Let’s consider a few examples.

When Flourish Schools came to us and said, “We are creating a microschool network based on joy and experiential learning,” we said, “Tell us more.” They explained, “We need faster and nimbler accreditation to make it available at no cost to families.” Through Next Generation Accreditation, Flourish has changed from not being open to doing breakthrough work with their first cohort of students.

As 12th graders receive admissions notices from early decision and early action applications, I’m thinking about the role of prestige in college admissions.

But I’m also thinking about it because last week I interviewed Jeff Selingo for Evolution Stories (episode to air in January).

Jeff’s latest best seller, Dream School, is a must-read on college admissions. It exposes the illusions of the prestige game while offering a playbook for thriving in college and beyond.

Dr. Brian Kelly, Head of School at the Carol Morgan School (Dominican Republic), faced this situation when launching the school’s new Arts, Innovation and Dining Center. When I interviewed Brian recently, he shared that his solution sprang from his early training in public relations.

Whatever this blog post’s title summons to mind for you, it is probably not the fashion show that I recently experienced at Pillar High School (NJ), a Middle States accredited school. But this fashion show reminded me of what the best schools do.

ACCREDITATION STORIES

In November, the Middle States Association accredited 15 microschools as part of our Next Generation Accreditation pilot. These schools might not have fit within a traditional accreditation model, yet they meet every one of MSA’s existing standards.

How? Through innovative models, adaptable practices, and deep purpose.

Back in October, I visited five of them across Tennessee. Here’s what I saw:

Middle States helped VHS become an accredited Learning Service Provider (LSP). LSPs represent a growing number of non-traditional educational organizations committed to quality, innovation, and continuous improvement. The VHS journey offers valuable takeaways for schools navigating partnerships and program expansion:

As a professional peer reviewer, you will see the entire system of a school in just three days. That is because Middle States standards and indicators map to every aspect of school operations—from daily classroom practices to long-term planning to foundational documents.

No other form of professional learning can enable you—in 3 short days!—to “see the system” of a school, and certainly not while embedding you in real time. It’s like high intensity cross-training. You may come to the team with experience in teaching and learning, but you’ll also learn about governance, finance, facilities, and other foundational elements of running a school. I wish I had participated on more visiting teams before I had become a Head of School the first time—nothing would have been better preparation.

TEACHER GROWTH + DEVELOPMENT

If you’re a classroom teacher, you might not look forward to professional development days– and I can’t blame you. But I can try to convince you that PD can be more than just a necessary fact of life—it can be powerful, effective, and good for you and your students.

What makes for a great learning experience? It’s actually simple: When learners apply the knowledge they’ve gained to real-world situations that genuinely matter to them.

That is why teachers should have the opportunity to participate in project-based professional development.

Reading detailed feedback is rewarding, but things get more interesting when we debrief peer visits. Having read all 24 pieces of feedback, the visited teacher leads the debrief, rather than being put under the microscope by their visitors. This allows them to ask clarifying and probing questions aligned with their growth priorities. We visitors act as teammates, helping the visited teacher to level up.

To be clear, shifting from a zero-sum to a positive-sum model of school won’t be easy. As one of my former colleagues likes to say, “Teachers cannot create an experience for students that those teachers themselves have not had.” So if we want to initiate a shift in our schools from a zero-sum to a positive-sum worldview, we should begin by inviting teachers into new professional learning and growth experiences.

This is precisely the moment that school leaders need to lean on what Michael Horn calls “tools of cooperation” in From Reopen to Reinvent. It’s not enough to have a powerful vision. It’s not enough even to know how you can get to that vision. As Horn says—and as I can confirm from experience earned the hard way—“Once a school leader has clarity around what they want to change, they still need to convince other individuals who will play a role in the change.”